Recently, I was reading an enjoyable Regency romance when I came across this description:

“He was strikingly handsome in his red coat. She could see the officer was a captain by the bars on his shoulders.”

Well, that popped me right out of the scene. Captains in the Napoleonic British Army, the various militias or any other continental army of the time did not have their rank designated by two metal bars on their shoulder tabs. Those are modern American Officer designations shown below: [Today’s British Army have similar insignia for their shoulder tabs]

There were no such metal insignia for distinguishing officer ranks in the Napoleonic British army. So, I decided to describe how ranks were displayed by the British [and basically all Napoleonic armies to some extent]

How were ranks displayed on British officers’ uniforms? Would you believe by the spacing of their coat buttons and lace?

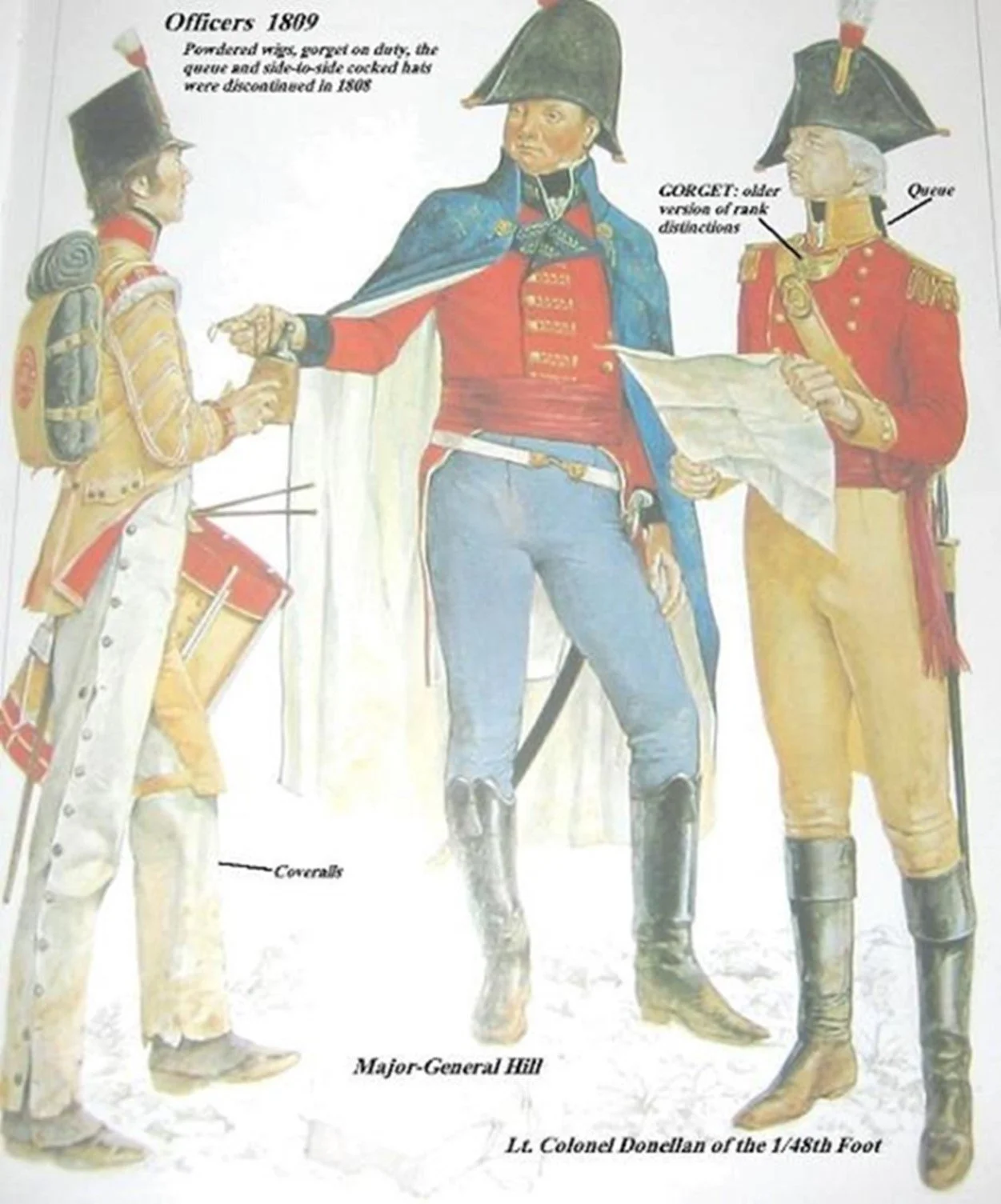

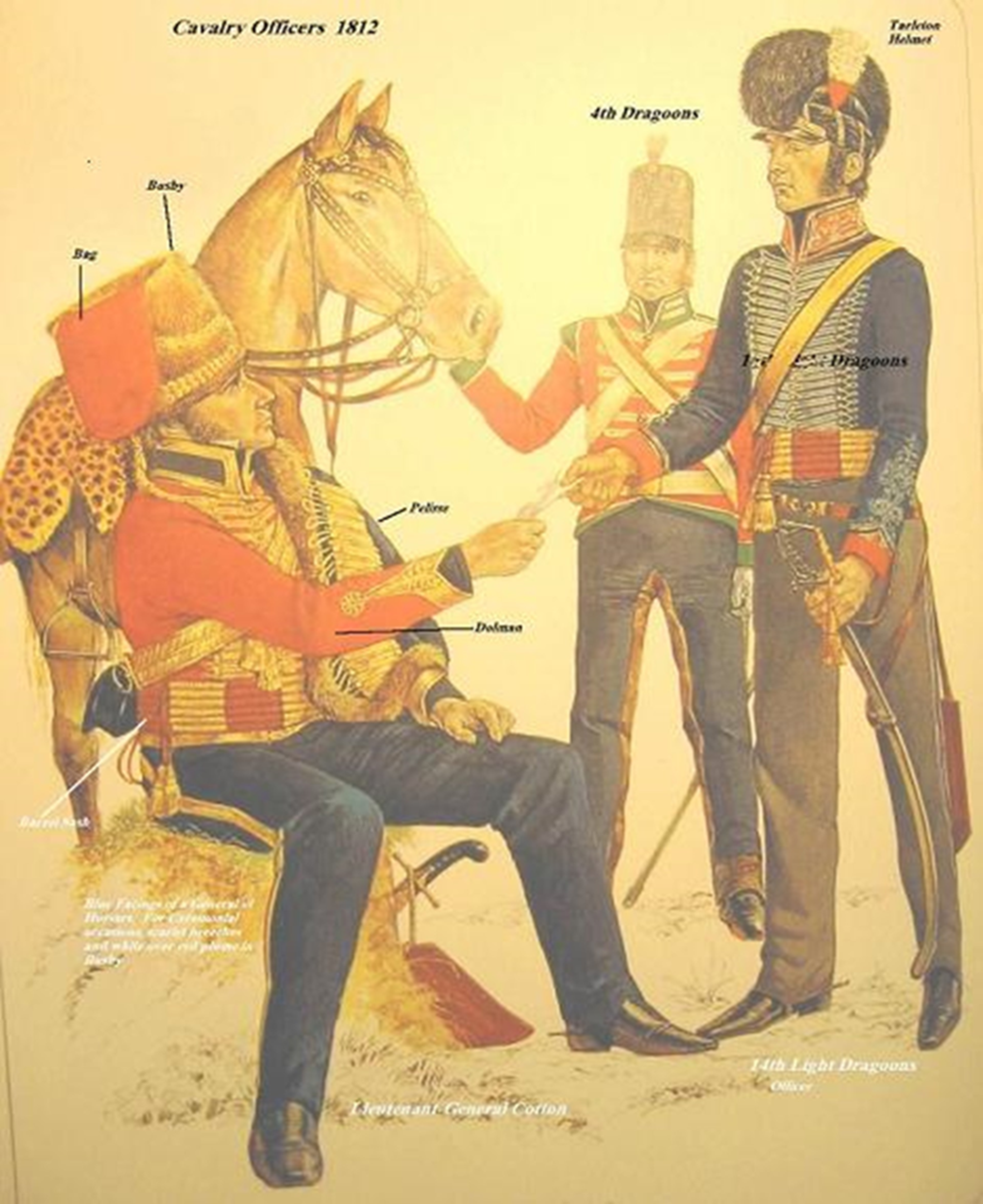

For officers, the signs of rank were evidenced on their coats. Look at the officers in the picture below to see if you can identify how their ranks are displayed without looking at the table farther down the page.

British militia had the same uniform and designations for rank. The difference between a Regular's uniform and a Militia man's was the absence of lace around the button holes on the front and sleeves of the coats. Militia uniforms were plain in comparison to the Regular officers.

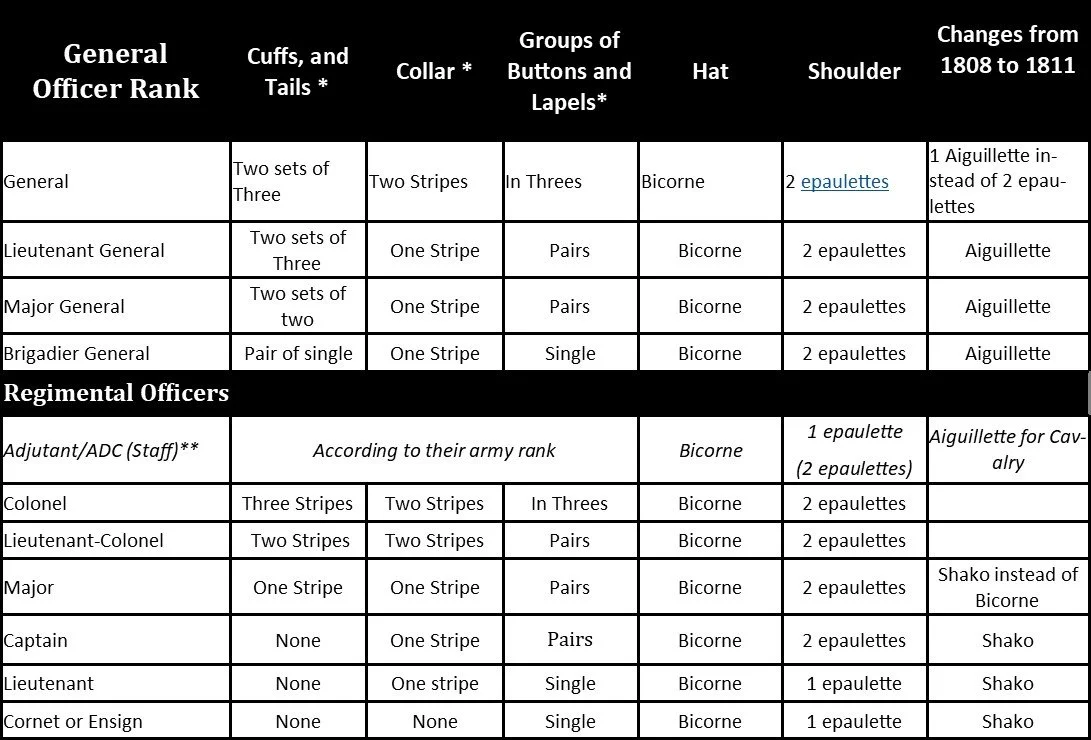

Here are the uniform regulations for British Officers for signifying their ranks from 1795 to 1815. All Infantry, artillery, engineers and general officers followed these conventions. Cavalry rank insignia tended to be more determined by the type of cavalry and each regiment’s uniform, thought the collar conventions generally were followed.

Notes:

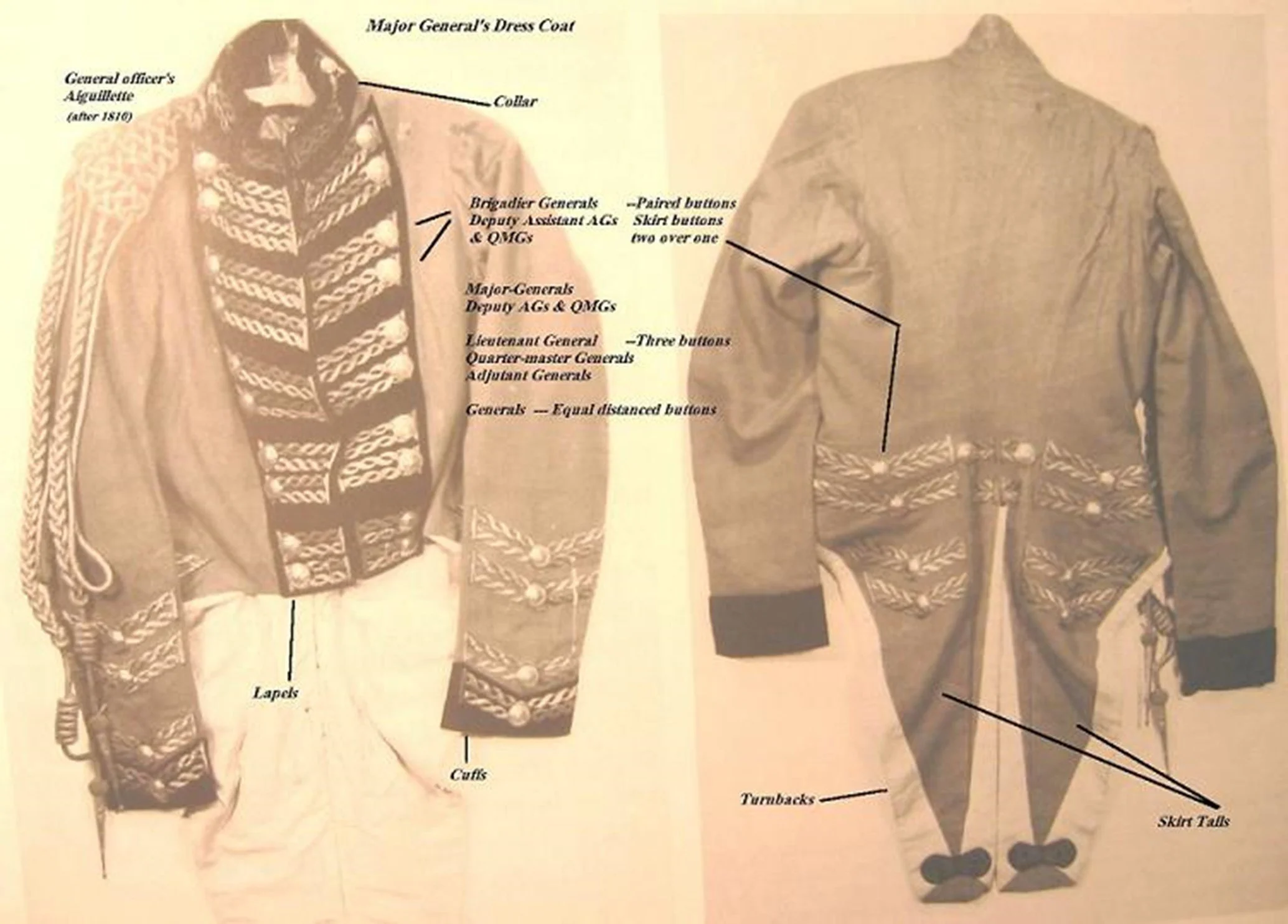

1. *The Stripes were chevrons of gold embroidery horizontally attached to cuffs, sleeves, collars, and tails. Each chevron had a button associated with it. On the lapels, the number of chevrons matched the number of buttons. [On the picture above, I’ve marked the parts of the uniform.] The plain or undress uniform coat did not display gold chevrons on the cuffs, as with General Hill shown above.

** General Staff- such as Quartermaster-General wore silver chevrons instead of gold on their coats, but their army rank was displayed. Quartermaster-General and Adjutant-General were staff positions, not ranks. George Murray was Wellington’s QG for most of the war and held the rank of Major General.

2. The Epaulettes of a colonel had a crown and star embroidered on the strap, the Lieutenant-Colonel a crown, and the Major a star. The same distinctions were observed by the field officers of the Light Dragoons.

3. A medal gorget was required around every officer’s neck, ensign to colonel. They were eliminated in 1808. The French Officers wore gorgets throughout the wars. They hated them.

4. The Bicorne was worn by regulation side-to-side (Napoleon style) until 1808 when it was decreed that it be worn fore-and-aft. (Wellington style) So, Colonel Donellan pictured above is wearing a pre-1808 uniform correctly. He was known for continuing to wear the gorget and powder his hair well into 1810.

5. The Aiguillette is the shoulder cording you see on the Major General’s coat seen above.

6. In actuality, you could see any combination of pre and post 1808 officer’s uniforms being worn through 1815.

7. The chevron embroidery was twice as wide for General officers. Each chevron, regardless of location, was supposed to have a button on the outside edge. The captain’s uniform was the only one where the match up between paired buttons and chevrons did not work. In that case the embroidery was placed between the two buttons. The two grades of officers where Regimental, up to colonel, and General, for Generals. This is what is meant by regimental officers or general officers.

8. There was an effort, though somewhat ineffectual, to associate a Regular Army regiment to a particular area or county--so the 15th Regiment was The 15th Shropshire. The idea was to have that county be the recruiting area for the regiment, but in practice it never really happened. A recruiting party paid no attention to such boundaries. However, part of the effort to connect the regiment to the county included the Militia regiment of the area sharing the same facing colors as the Regular regiment.

9. Field-Marshals could wear whatever they pleased, but officially, it would be red with dark blue facings, and lots and lots of gold braid and cording, particularly on the color and cuffs, so that the color blue could be hardly seen. Wellington tended to wear a blue overcoat on campaign.

Wellington uniformed as a field marshal. The blue sash is worn by the field marshal.

[I just saw the PBS Colin Firth version of Pride and Prejudice again, and at the end in the wedding, there is Darcy’s cousin in an accurate Lt. Colonel’s dress uniform]

See if you can identify the ranks of the following two regimental officers using the table of rank designations above:

1.

2.

1. The officer is a full colonel, three buttons in a group on his coat and sleeves and two epaulettes.

2. The officer is a lieutenant, single buttons spacing, one chevon on the collar and one epaulette. The illustration is inaccurate because the lieutenant is wearing the bicorne fore and aft, but still wearing a gorget. Note that both officers have another emblem of rank for all regimental officers and NCOs, a red sash.

For the Cavalry, the rank distinctions followed the same patterns, but become more problematic. In general, the lace for officers was silver when the enlisted man’s uniform cording was white, and gold if the enlisted man’s cording was yellow. The number of layers of gold or silver embroidery and cording at the cuff and collar denoted the rank of the officer, ensigns with no collar cording, otherwise like the lieutenant’s single cord, captains two, majors three and so forth. For generals, they were supposed to wear staff uniforms following the infantry pattern, but each cavalry type, dragoon, hussar and Guard Dragoon and Household horse had a recognized “General officer’s Uniform” simply because even Generals liked dashing uniforms. Lord Uxbridge wore the officer’s uniform of the 7th Hussars at Waterloo. The picture above of General Cotton’s General of Hussars uniform he wore in the Peninsula. It is recognizable because of the dark blue cuffs and collar of a General—as there were no 'royal hussars' with dark blue facings. Of course, he was known for his extravagant outfits so there is a lot of fancy gold braiding.

Note in the picture above, the light dragoon trooper handing Cotton the note is an officer, having silver lace and cuff embroidery. As many officers were wealthy and all officers were responsible for supplying their own uniforms, there could be a lot of self expression among both infantry and cavalry officers, and little policing of the materials or final results was done as long as the rank and regiment colors were recognizable and the uniform not ‘too’ flamboyant. [i.e. looked so fancy as to rival the higher-ranked officers] Therefore, one could see a great deal of diversity around the edges of the printed regulations, particularly among the higher ranks. Here is the Captain Grose’s 1795 take on that issue in his popular humor book “Advice to Officers.” His advice is addressed ‘To Young Officers:’

“The first article we shall consider is your dress; a taste in which is the most distinguishing mark of military genius, and the principal characteristic of a good officer… The fashion of your clothes must depend on that ordered in the corps; that is to say, must be in direct opposition to it: for it would shew a deplorable poverty of genius, if you had not some ideas of your own in dress.”

Grose’s book remained in print well into the 1800s. Obviously, as the nineteenth century wore on, [pun intended] uniforms became, well, more uniform. The chevrons on some officers’ collars were transferred to the shoulder tabs. As the military took over responsibility for clothing officers, far less expensive, smaller metal badges replaced the heavily embroidered officer decorations. Today, only high-ranking generals and 20th century military dictators regularly wear any kind of embroidered gold, fancy belts and cuff decorations.